Lecture 6: MLOps Infrastructure & Tooling

Video

Slides

Notes

Lecture by Sergey Karayev. Notes transcribed by James Le and Vishnu Rachakonda.

1 - Dream vs. Reality for ML Practitioners

The dream of ML practitioners is that we are provided the data, and somehow we build an optimal machine learning prediction system available as a scalable API or an edge deployment. That deployment then generates more data for us, which can be used to improve our system.

The reality is that you will have to:

- Aggregate, process, clean, label, and version the data

- Write and debug model code

- Provision compute

- Run many experiments and review the results

- Discover that you did something wrong or maybe try a different architecture -> Write more code and provision more compute

- Deploy the model when you are happy

- Monitor the predictions that the model makes on production data so that you can gather some good examples and feed them back to the initial data flywheel loop

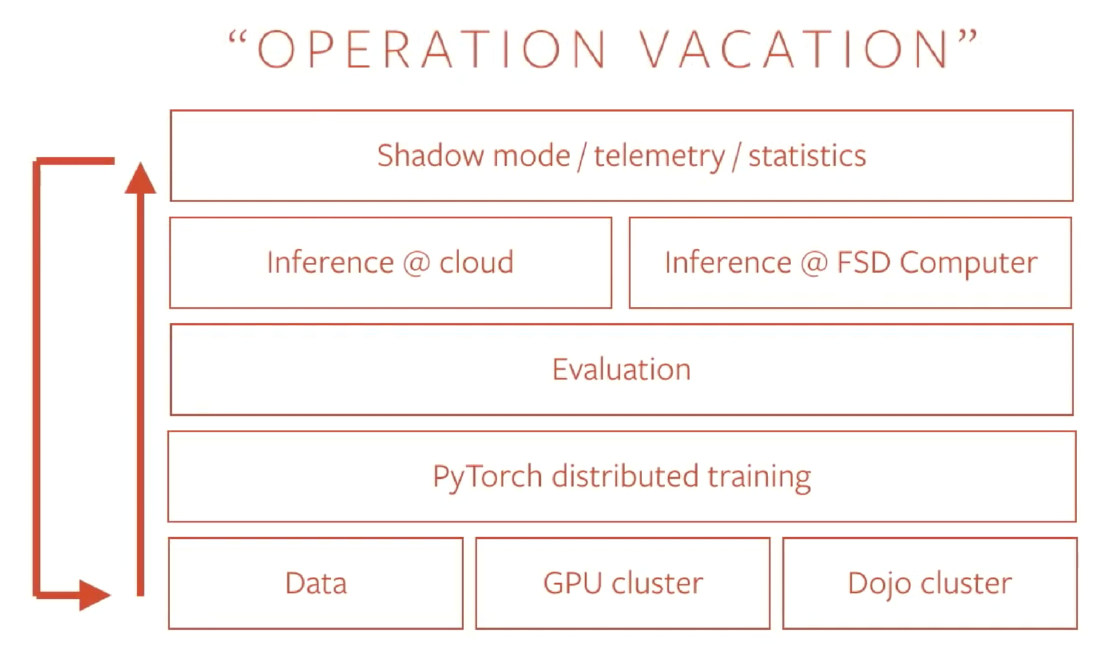

For example, the slide above is from Andrej Karpathy’s talk at PyTorch Devcon 2019 discussing Tesla’s self-driving system. Their dream is to build a system that goes from the data gathered through their training, evaluation, and inference processes and gets deployed on the cars. As people drive, more data will be collected and added back to the training set. As this process repeats, Tesla’s ML engineers can all go on vacation :)

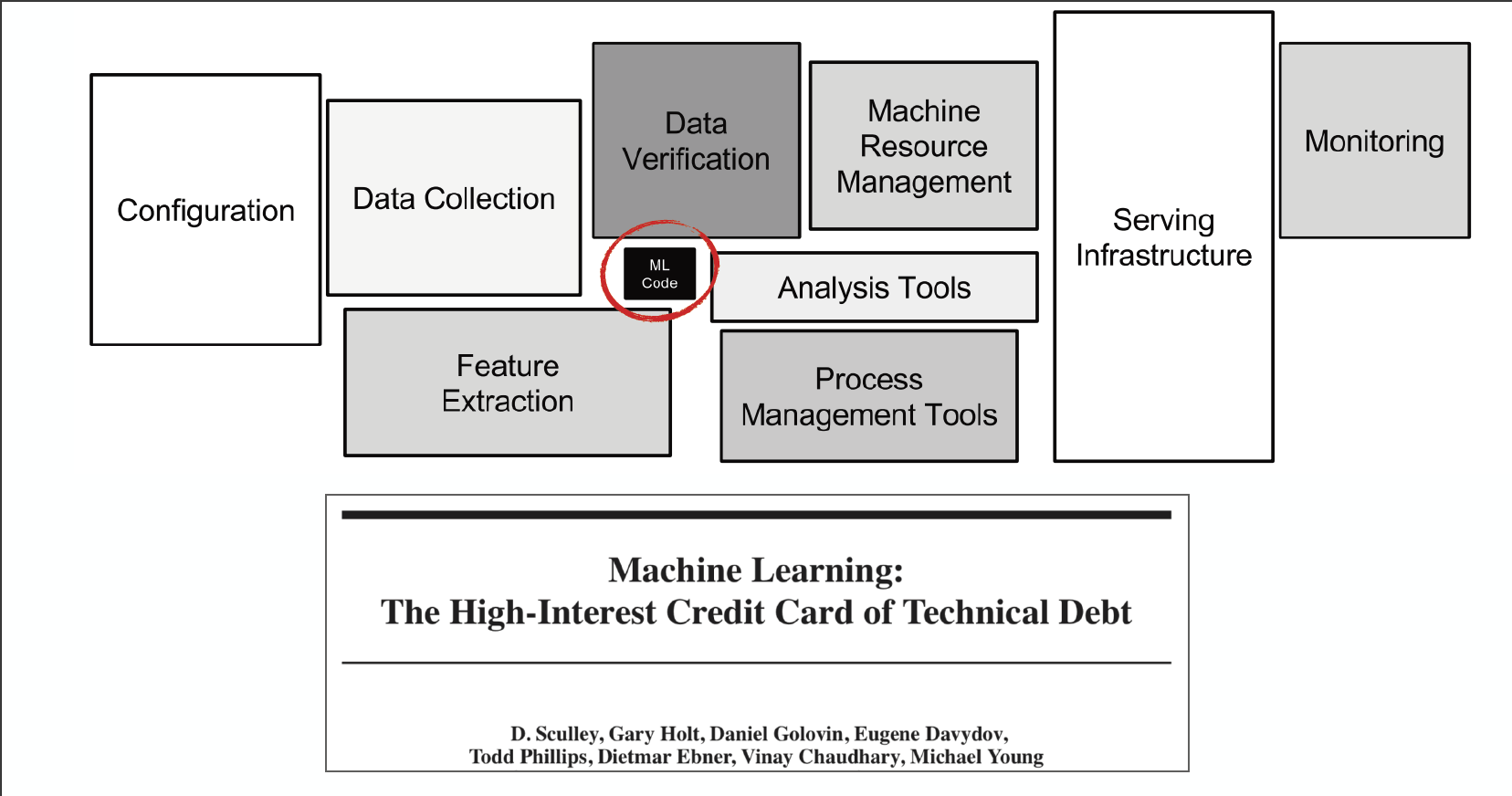

The picture above (from the famous Google paper “Machine Learning: The High-Interest Credit Card of Technical Debt”) shows that the ML code portion in a real-world ML system is a lot smaller than the infrastructure needed for its support. As ML projects move from small-scale research experiments to large-scale industry deployments, your organization most likely will require a massive amount of infrastructure to support large inferences, distributed training, data processing pipelines, reproducible experiments, model monitoring, etc.

2 - Three Buckets of Tooling Landscape

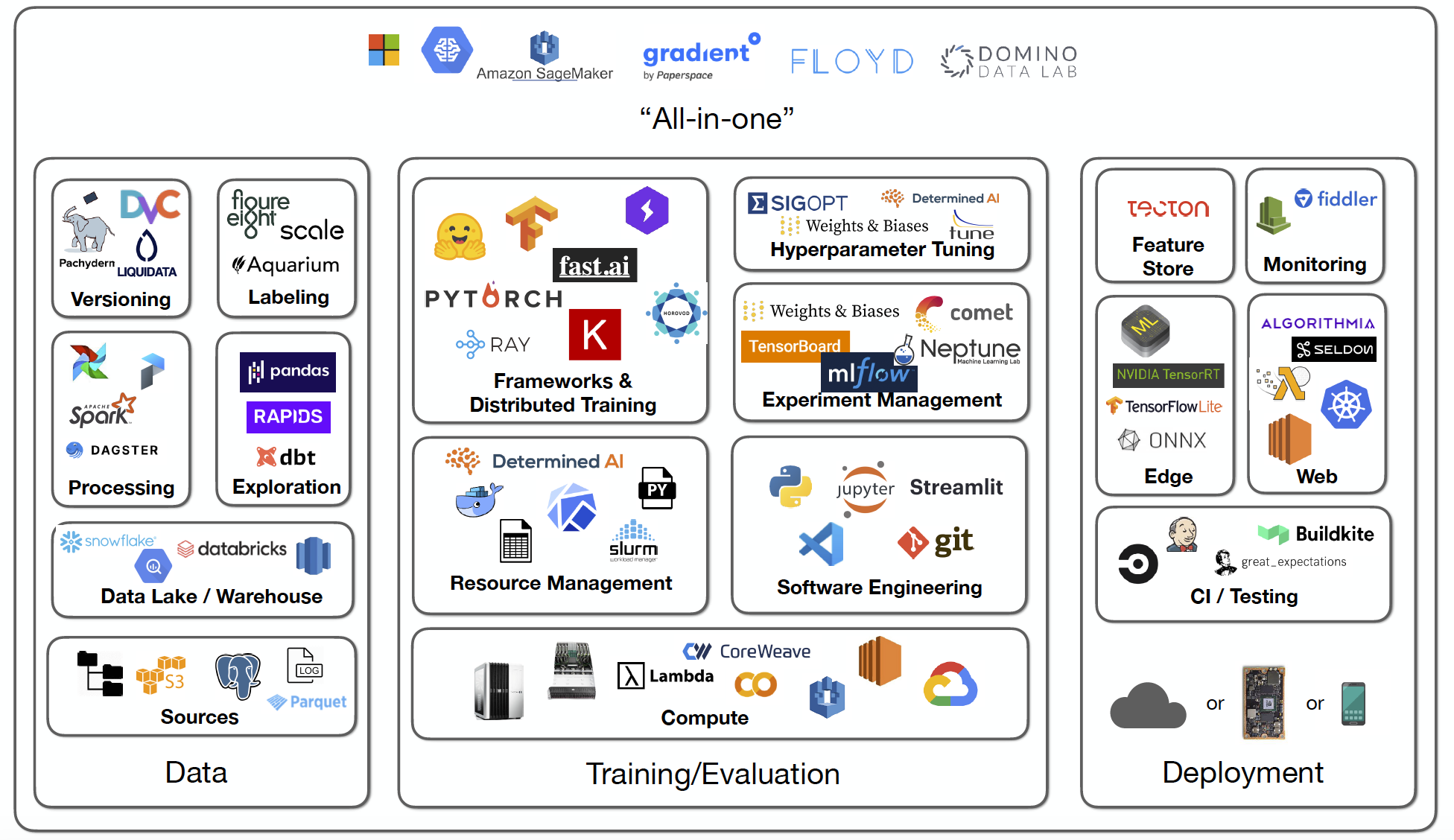

We can break down the landscape of all this necessary infrastructure into three buckets: data, training/evaluation, and deployment.

- The data bucket includes the data sources, data lakes/warehouses, data processing, data exploration, data versioning, and data labeling.

- The training/evaluation bucket includes compute sources, resource management, software engineering, frameworks and distributed training libraries, experiment management, and hyper-parameter tuning.

- The deployment bucket includes continuous integration and testing, edge deployment, web deployment, monitoring, and feature store.

There are also several vendors offering “all-in-one” MLOps solutions that cover all three buckets. This lecture focuses on the training/evaluation bucket.

3 - Software Engineering

When it comes to writing deep learning code, Python is the clear programming language of choice. As a general-purpose language, Python is easy to learn and easily accessible, enabling you to find skilled developers on a faster basis. It has various scientific libraries for data wrangling and machine learning (Pandas, NumPy, Scikit-Learn, etc.). Regardless of whether your engineering colleagues write code in a lower-level language like C, C++, or Java, it is generally neat to join different components with a Python wrapper.

When choosing your IDEs, there are many options out there (Vim, Emacs, Sublime Text, Jupyter, VS Code, PyCharm, Atom, etc.). Each of these has its uses in any application, and you’re better to switch between them to remain agile without relying heavily on shortcuts and packages. It also helps teams work better if they can jump into different IDEs and comment/collaborate with other colleagues. In particular, Visual Studio Code makes for a very nice Python experience, where you have access to built-in git staging and diffing, peek at documentation, linter code as you write, and open projects remotely.

Jupyter Notebooks have rapidly grown in popularity among data scientists to become the standard for quick prototyping and exploratory analysis. For example, Netflix based all of their machine learning workflows on them, effectively building a whole notebook infrastructure to leverage them as a unifying layer for scheduling workflows. Jeremy Howard develops his fast.ai codebase entirely with notebooks and introduces a project called nbdev that shows people how to develop well-tested code in a notebook environment.

However, there are many problems with using notebooks as a last resort when working in teams that aim to build machine/deep learning products. Alexander Mueller's blog post outlines the five reasons why they suck:

- It is challenging to enable good code versioning because notebooks are big JSON files that cannot be merged automatically.

- Notebook “IDE” is primitive, as they have no integration, no lifting, and no code-style correction. Data scientists are not software engineers, and thus, tools that govern their code quality and help improve it are very important.

- It is very hard to structure code reasonably, put code into functions, and develop tests while working in notebooks. You better develop Python scripts based on test-driven development principles as soon as you want to reproduce some experiments and run notebooks frequently.

- Notebooks have out-of-order execution artifacts, meaning that you can easily destroy your current working state when jumping between cells of notebooks.

- It is also difficult to run long or distributed tasks. If you want to handle big datasets, better pull your code out of notebooks, start a Python folder, create fixtures, write tests, and then deploy your application to a cluster.

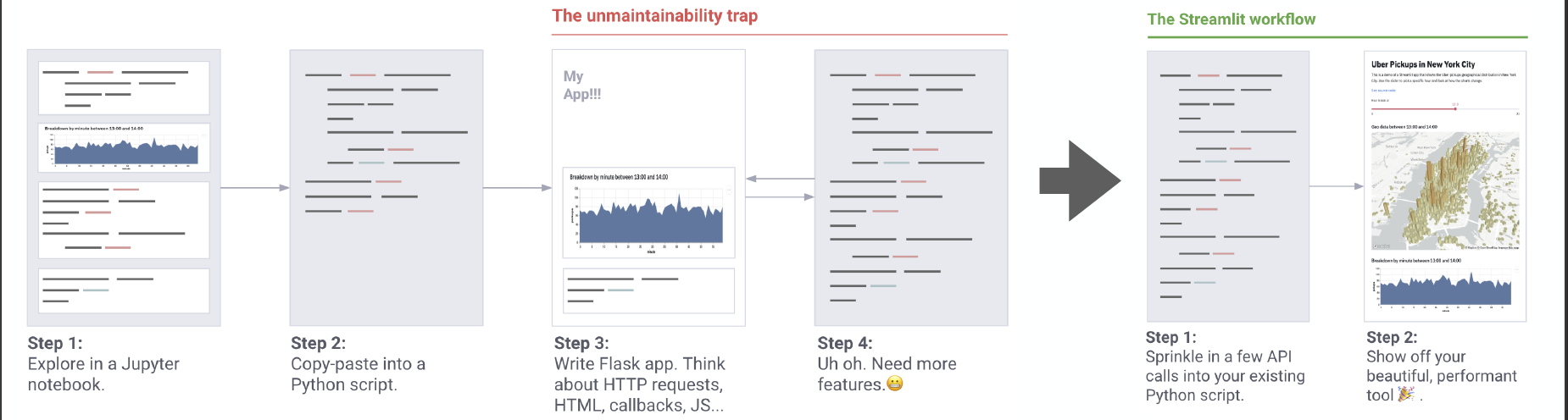

Recently, a new application framework called Streamlit was introduced. The creators of the framework wanted machine learning engineers to be able to create beautiful apps without needing a tools team; in other words, these internal tools should arise as a natural byproduct of the machine learning workflow. According to the launch blog post, here are the core principles of Streamlit:

- Embrace Python scripting: Streamlit apps are just scripts that run from top to bottom. There’s no hidden state. You can factor your code with function calls. If you know how to write Python scripts, you can write Streamlit apps.

- Treat widgets as variables: There are no callbacks in Streamlit. Every interaction simply reruns the script from top to bottom. This approach leads to a clean codebase.

- Reuse data and computation: Streamlit introduces a cache primitive that behaves like a persistent, immutable-by-default data store that lets Streamlit apps safely and effortlessly reuse information.

Right now, Streamlit is building features that enable sharing machine learning projects to be as easy as pushing a web app to Heroku.

We recommend using conda to set up your Python and CUDA environments and pip-tools to separate mutually compatible versions of all requirements for our lab.

4 - Compute Hardware

We can break down the compute needs into an early-stage development step and a late-stage training/evaluation step.

- During the development stage, we write code, debug models, and look at the results. It’d be nice to be able to compile and train models via an intuitive GUI quickly.

- During the training/evaluation stage, we design model architecture, search for hyper-parameters, and train large models. It’d be nice to launch experiments and review results easily.

Compute matters with each passing year due to the fact that the results came out of deep learning are using more and more compute (check out this 2018 report from OpenAI). Looking at recent Transformer models, while OpenAI’s GPT-3 has not been fully commercialized yet, Google already released the Switch Transformer with orders of magnitude larger in the number of parameters.

So should you get your own hardware, go straight to the cloud, or use on-premise options?

GPU Basics

This is basically an NVIDIA game, as they are the only provider of good deep learning GPUs. However, Google’s TPUs are the fastest, which is available only on GCP.

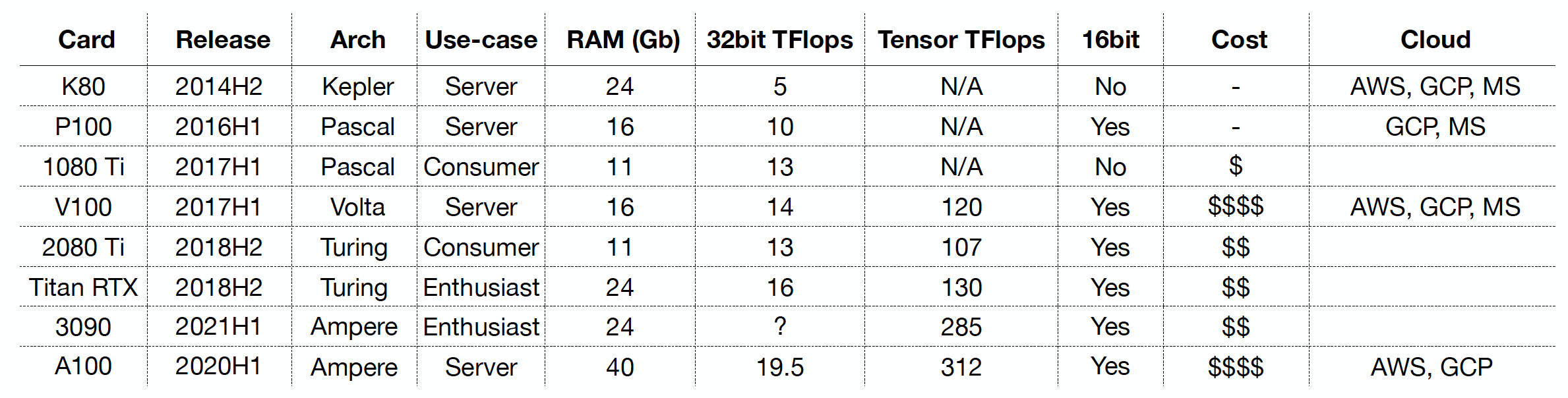

There is a new NVIDIA architecture every year: Kepler -> Pascal -> Volta -> Turing -> Ampere. NVIDIA often released the server version of the cards first, then the “enthusiast” version, and finally the consumer version. If you use these cards for business purposes, then you suppose to use the server version.

GPUs have a different amount of RAM. You can only compute on the data that is on the GPU memory. The more data you can fit on the GPU, the larger your batches are, the faster your training goes.

For deep learning, you use 32-bit precision. In fact, starting with the Volta architecture, NVIDIA developed tensor cores that are specifically designed for deep learning operations (mixed-precision between 32 and 16 bit). Tensor Cores reduce the used cycles needed for calculating multiply and addition operations and the reliance on repetitive shared memory access, thus saving additional cycles for memory access. This is very useful for the convolutional/Transformer models that are prevalent nowadays.

Let’s go through different GPU architectures:

- Kepler/Maxwell: They are 2-4x slower than the Pascal/Volta ones below. You should not buy these old guards (K80).

- Pascal: They are in the 1080 Ti cards from 2017, which are still useful if bought used (especially for recurrent neural networks). P100 is the equivalent cloud offering.

- Volta/Turing: These are the preferred choices over the Kepler and Pascal because of their support for 16-bit mixed-precision via tensor cores. Hardware options are 2080 Ti and Titan RTX, while the cloud option is V100.

- Ampere: This architecture is available in the latest hardware (3090) and cloud (A100) offerings. They have the most tensor cores, leading to at least 30% speedup over Turing.

You can check out this recent GPU benchmark from Lambda Labs and consult Tim Dettmers’ advice on which GPUs to get.

Cloud Options

Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform, and Microsoft Azure are the cloud heavyweights with largely similar functions and prices. There are also startups like Lambda Labs and Corewave that provide cloud GPUs.

On-Prem Options

You can either build your own or buy pre-built devices from vendors like Lambda Labs, NVIDIA, Supermicro, Cirrascale, etc.

Recommendations

Even though the cloud is expensive, it’s hard to make on-prem devices scale past a certain point. Furthermore, dev-ops things are easier to be done in the cloud than to be set up by yourself. And if your machine dies or requires maintenance, that will be a constant headache if you are responsible for managing it.

Here are our recommendations for three profiles:

- Hobbyists: Build your own machine (maybe a 4x Turing or a 2x Ampere PC) during development. Either use the same PC or use cloud instances during training/evaluation.

- Startups: Buy a sizeable Lambda Labs machine for every ML scientist during development. Buy more shared server machines or use cloud instances during training/evaluation.

- Larger companies: Buy an even more powerful machine for every ML scientist during development. Use cloud with fast instances with proper provisioning and handling of failures during training/evaluation.

5 - Resource Management

With all the resources we have discussed (compute, dependencies, etc.), our challenge turns to manage them across the specific use cases we may have. Across all the resources, our goal is always to be able to easily experiment with the necessary resources to achieve the desired application of ML for our product.

For this challenge of allocating resources to experimenting users, there are some common solutions:

- Script a solution ourselves: In theory, this is the simplest solution. We can check if a resource is free and then lock it if a particular user is using it or wants to.

- SLURM: If we don't want to write the script entirely ourselves, standard cluster job schedulers like SLURM can help us. The workflow is as follows: First, a script defines a job’s requirements. Then, the SLURM queue runner analyzes this and then executes the jobs on the correct resource.

- Docker/Kubernetes: The above approach might still be too manual for your needs, in which case you can turn to Docker/Kubernetes. Docker packages the dependency stack into a lighter-than-VM package called a container (that excludes the OS). Kubernetes lets us run these Docker containers on a cluster. In particular, Kubeflow is an OSS project started by Google that allows you to spawn/manage Jupyter notebooks and manage multi-step workflows. It also has lots of plug-ins for extra processes like hyperparameter tuning and model deployment. However, Kubeflow can be a challenge to setup.

- Custom ML software: There’s a lot of novel work and all-in-one solutions being developed to provision compute resources for ML development efficiently. Platforms like AWS Sagemaker, Paperspace Gradient, and Determined AI are advancing. Newer startups like Anyscale and Grid.AI (creators of PyTorch Lightning) are also tackling this. Their vision is around allowing you to seamlessly go from training models on your computer to running lots of training jobs in the cloud with a simple set of SDK commands.

6 - Frameworks and Distributed Training

Deep Learning Frameworks

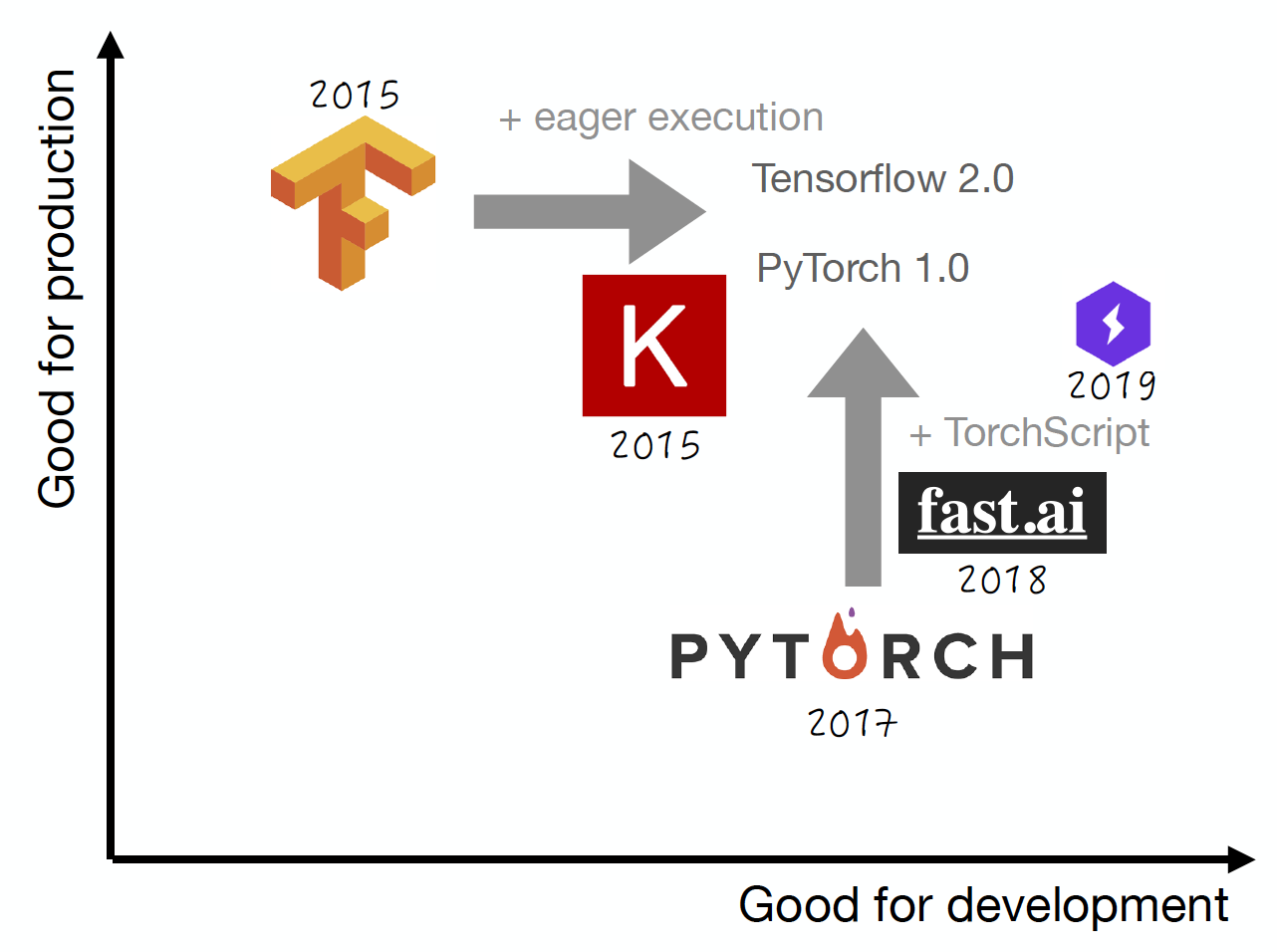

If you’ve built a deep learning model in the last few years, you’ve probably used a deep learning framework. Frameworks like TensorFlow have crucially shaped the development of the deep learning revolution. The reality is that deep learning frameworks have existed for a while. Projects like Theano and Torch have been around for 10+ years. In contemporary use, there are three main frameworks we’ll focus on - TensorFlow, Keras, and PyTorch. We evaluate frameworks based on their utility for production and development.

When TensorFlow came out in 2015, it was billed heavily as a production-optimized DL framework with an underlying static optimized graph that could be deployed across compute environments. However, TF 1.0 had a pretty unpleasant development experience; in addition to developing your models, you had to consider the underlying execution graph you were describing. This kind of “meta-development” posed a challenge for newcomers. The Keras project solved many of these issues by offering a simpler way to define models, and eventually became a part of TensorFlow. PyTorch, when it was introduced in 2017, offered a polar opposite to TensorFlow. It made development super easy by consisting almost exclusively of simple Python commands, but was not designed to be fast at scale.

Using TF/Keras or PyTorch is the current recommended way to build deep learning models unless you have a powerful reason not to. Essentially, both have converged to pretty similar points that balance development and production. TensorFlow adopted eager execution by default and became a lot easier to develop quickly in. PyTorch subsumed Caffe2 and became much faster as a result, specifically by adding the ability to compile speedier model artifacts. Nowadays, PyTorch has a lot of momentum, likely due to its ease of development. Newer projects like fast.ai and PyTorch Lighting add best practices and additional functionality to PyTorch, making it even more popular. According to this 2018 article on The Gradient, more than 80% of submissions are in PyTorch in academic projects.

All these frameworks may seem like excessive quibbling, especially since PyTorch and TensorFlow have converged in important ways. Why do we even require such extensive frameworks?

It’s theoretically possible to define entire models and their required matrix math (e.g., a CNN) in NumPy, the classic Python numerical computing library. However, we quickly run into two challenges: back-propagating errors through our model and running the code on GPUs, which are powerful computation accelerators. For these issues to be addressed, we need frameworks to help us with auto-differentiation, an efficient way of computing the gradients, and software compatibility with GPUs, specifically interfacing with CUDA. Frameworks allow us to abstract the work required to achieve both features, while also layering in valuable abstractions for all the latest layer designs, optimizers, losses, and much more. As you can imagine, the abstractions offered by frameworks save us valuable time on getting our model to run and allow us to focus on optimizing our model.

New projects like JAX and HuggingFace offer different or simpler abstractions. JAX focuses primarily on fast numerical computation with autodiff and GPUs across machine learning use cases (not just deep learning). HuggingFace abstracts entire model architectures in the NLP realm. Instead of loading individual layers, HuggingFace lets you load the entirety of a contemporary mode (along with weights)l like BERT, tremendously speeding up development time. HuggingFace works on both PyTorch and TensorFlow.

Distributed Training

Distributed training is a hot topic as the datasets and the models we train become too large to work on a single GPU. It’s increasingly a must-do. The important thing to note is that distributed training is a process to conduct a single model training process; don’t confuse it with training multiple models on different GPUs. There are two approaches to distributed training: data parallelism and model parallelism.

Data Parallelism

Data parallelism is quite simple but powerful. If we have a batch size of X samples, which is too large for one GPU, we can split the X samples evenly across N GPUs. Each GPU calculates the gradients and passes them to a central node (either a GPU or a CPU), where the gradients are averaged and backpropagated through the distributed GPUs. This paradigm generally results in a linear speed-up time (e.g., two distributed GPUs results in a ~2X speed-up in training time). In modern frameworks like PyTorch, PyTorch Lightning, and even in schedulers like SLURM, data-parallel training can be achieved simply by specifying the number of GPUs or calling a data parallelism-enabling object (e.g., torch.nn.DataParallel). Other tools like Horovod (from Uber) use non-framework-specific ways of enabling data parallelism (e.g., MPI, a standard multiprocessing framework). Ray, the original open-source project from the Anyscale team, was designed to enable general distributed computing applications in Python and can be similarly applied to data-parallel distributed training.

Model Parallelism

Model parallelism is a lot more complicated. If you can’t fit your entire model’s weights on a single GPU, you can split the weights across GPUs and pass data through each to train the weights. This usually adds a lot of complexity and should be avoided unless absolutely necessary. A better solution is to pony up for the best GPU available, either locally or in the cloud. You can also use gradient checkpointing, a clever trick wherein you write some gradients to disk as you compute them and load them only as you need them for updates. New work is coming out to make this easier (e.g., research and framework maturity).

7 - Experiment Management

As you run numerous experiments to refine your model, it’s easy to lose track of code, hyperparameters, and artifacts. Model iteration can lead to lots of complexity and messiness. For example, you could be monitoring the learning rate’s impact on your model’s performance metric. With multiple model runs, how will you monitor the impact of the hyperparameter?

A low-tech way would be to manually track the results of all model runs in a spreadsheet. Without great attention to detail, this can quickly spiral into a messy or incomplete artifact. Dedicated experiment management platforms are a remedy to this issue. Let’s cover a few of the most common ones:

- TensorBoard: This is the default experiment tracking platform that comes with TensorFlow. As a pro, it’s easy to get started with. On the flip side, it’s not very good for tracking and comparing multiple experiments. It’s also not the best solution to store past work.

- MLFlow: An OSS project from Databricks, MLFlow is a complete platform for the ML lifecycle. They have great experiment and model run management at the core of their platform. Another open-source project, Keepsake, recently came out focused solely on experiment tracking.

- Paid platforms (Comet.ml, Weights and Biases, Neptune): Finally, outside vendors offer deep, thorough experiment management platforms, with tools like code diffs, report writing, data visualization, and model registering features. In our labs, we will use Weights and Biases.

8 - Hyperparameter Tuning

To finalize models, we need to ensure that we have the optimal hyperparameters. Since hyperparameter optimization (as this process is called) can be a particularly compute-intensive process, it’s useful to have software that can help. Using specific software can help us kill underperforming model runs with bad hyperparameters early (to save on cost) or help us intelligently sweep ranges of hyperparameter values. Luckily, there’s an increasing number of software providers that do precisely this:

- SigOpt offers an API focused exclusively on efficient, iterative hyperparameter optimization. Specify a range of values, get SigOpt’s recommended hyperparameter settings, run the model and return the results to SigOpt, and repeat the process until you’ve found the best parameters for your model.

- Rather than an API, Ray Tune offers a local software (part of the broader Ray ecosystem) that integrates hyperparameter optimization with compute resource allocation. Jobs are scheduled with specific hyperparameters according to state-of-the-art methods, and underperforming jobs are automatically killed.

- Weights and Biases also has this feature! With a YAML file specification, we can specify a hyperparameter optimization job and perform a “sweep,” during which W&B sends parameter settings to individual “agents” (our machines) and compares performance.

9 - “All-In-One” Solutions

Some platforms integrate all the aspects of the applied ML stack we’ve discussed (experiment tracking, optimization, training, etc.) and wrap them into a single experience. To support the “lifecycle,” these platforms typically include:

- Labeling and data querying services

- Model training, especially though job scaling and scheduling

- Experiment tracking and model versioning

- Development environments, typically through notebook-style interfaces

- Model deployment (e.g., via REST APIs) and monitoring

One of the earliest examples of such a system is Facebook’s FBLearner (2016), which encompassed data and feature storage, training, inference, and continuous learning based on user interactions with the model’s outputs. You can imagine how powerful having one hub for all this activity can be for ML application and development speed. As a result, cloud vendors (Google, AWS, Azure) have developed similar all-in-one platforms, like Google Cloud AI Platform and AWS SageMaker. Startups like Paperspace Gradient, Neptune, and FloydHub also offer all-in-one platforms focused on deep learning. Determined AI, which focuses exclusively on the model development and training part of the lifecycle, is the rare open-source platform in this space. Domino Data Lab is a traditional ML-focused startup with an extensive feature set worth looking at. It’s natural to expect more MLOps (as this kind of tooling and infra is referred to) companies and vendors to build out their feature set and become platform-oriented; Weights and Biases is a good example of this.

In conclusion, take a look at the below table to compare a select number of MLOps platform vendors. Pricing is quite variable.

Staying up to date across all the tooling can be a real challenge, but check out FSDL’s Tooling Tuesdays on Twitter as a starting point!

We are excited to share this course with you for free.

We have more upcoming great content. Subscribe to stay up to date as we release it.

We take your privacy and attention very seriously and will never spam you. I am already a subscriber