Lecture 5: ML Projects

Learn how to set up Machine Learning projects like a pro. This includes an understanding of the ML lifecycle, an acute mind of the feasibility and impact, an awareness of the project archetypes, and an obsession with metrics and baselines.

Video

Slides

Notes

Lecture by Josh Tobin. Notes transcribed by James Le and Vishnu Rachakonda.

1 - Why Do ML Projects Fail?

Based on a report from TechRepublic a few years back, despite increased interest in adopting machine learning (ML) in the enterprise, 85% of machine learning projects ultimately fail to deliver on their intended promises to business. Failure can happen for many reasons; however, a few glaring dangers will cause any AI project to crash and burn.

-

ML is still very much a research endeavor. Therefore it is very challenging to aim for a 100% success rate.

-

Many ML projects are technically infeasible or poorly scoped.

-

Many ML projects never leap production, thus getting stuck at the prototype phase.

-

Many ML projects have unclear success criteria because of a lack of understanding of the value proposition.

-

Many ML projects are poorly managed because of a lack of interest from leadership.

2 - Lifecycle

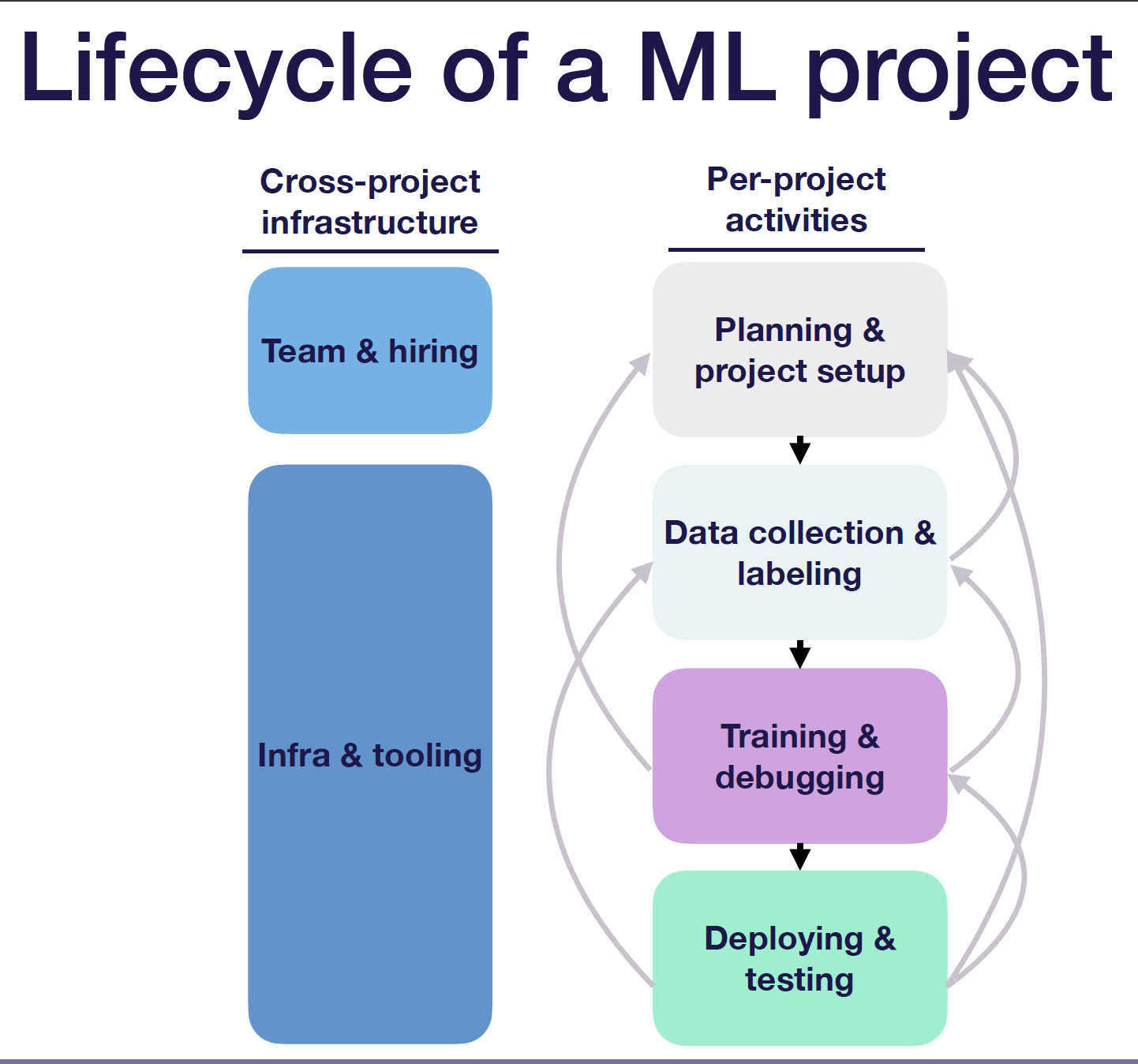

It’s essential to understand what constitutes all of the activities in a machine learning project. Typically speaking, there are four major phases:

-

Planning and Project Setup: At this phase, we want to decide the problem to work on, determine the requirements and goals, figure out how to allocate resources properly, consider the ethical implications, etc.

-

Data Collection and Labeling: At this phase, we want to collect training data and potentially annotate them with ground truth, depending on the specific sources where they come from. We may find that it’s too hard to get the data, or it might be easier to label for a different task. If that’s the case, go back to phase 1.

-

Model Training and Model Debugging: At this phase, we want to implement baseline models quickly, find and reproduce state-of-the-art methods for the problem domain, debug our implementation, and improve the model performance for specific tasks. We may realize that we need to collect more data or that labeling is unreliable (thus, go back to phase 2). Or we may recognize that the task is too challenging and there is a tradeoff between project requirements (thus, go back to phase 1).

-

Model Deploying and Model Testing: At this phase, we want to pilot the model in a constrained environment (i.e., in the lab), write tests to prevent regressions, and roll the model into production. We may see that the model doesn’t work well in the lab, so we want to keep improving the model’s accuracy (thus, go back to phase 3). Or we may want to fix the mismatch between training data and production data by collecting more data and mining hard cases (thus go back to phase 2). Or we may find out that the metric picked doesn’t actually drive downstream user behavior, and/or performance in the real world isn’t great. In such situations, we want to revisit the projects’ metrics and requirements (thus, go back to phase 1).

Besides the per-project activities mentioned above, there are two other things that any ML team will need to solve across any projects they get involved with: (1) building the team and hiring people; and (2) setting up infrastructure and tooling to build ML systems repeatedly and at scale.

Additionally, it might be useful to understand state-of-the-art results in your application domain so that you know what’s possible and what to try next.

3 - Prioritizing Projects

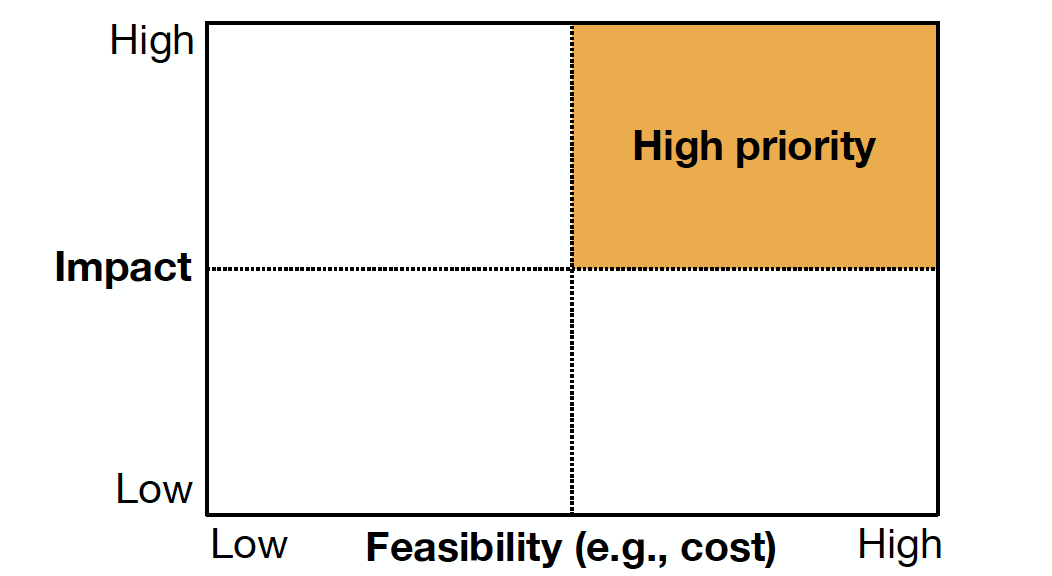

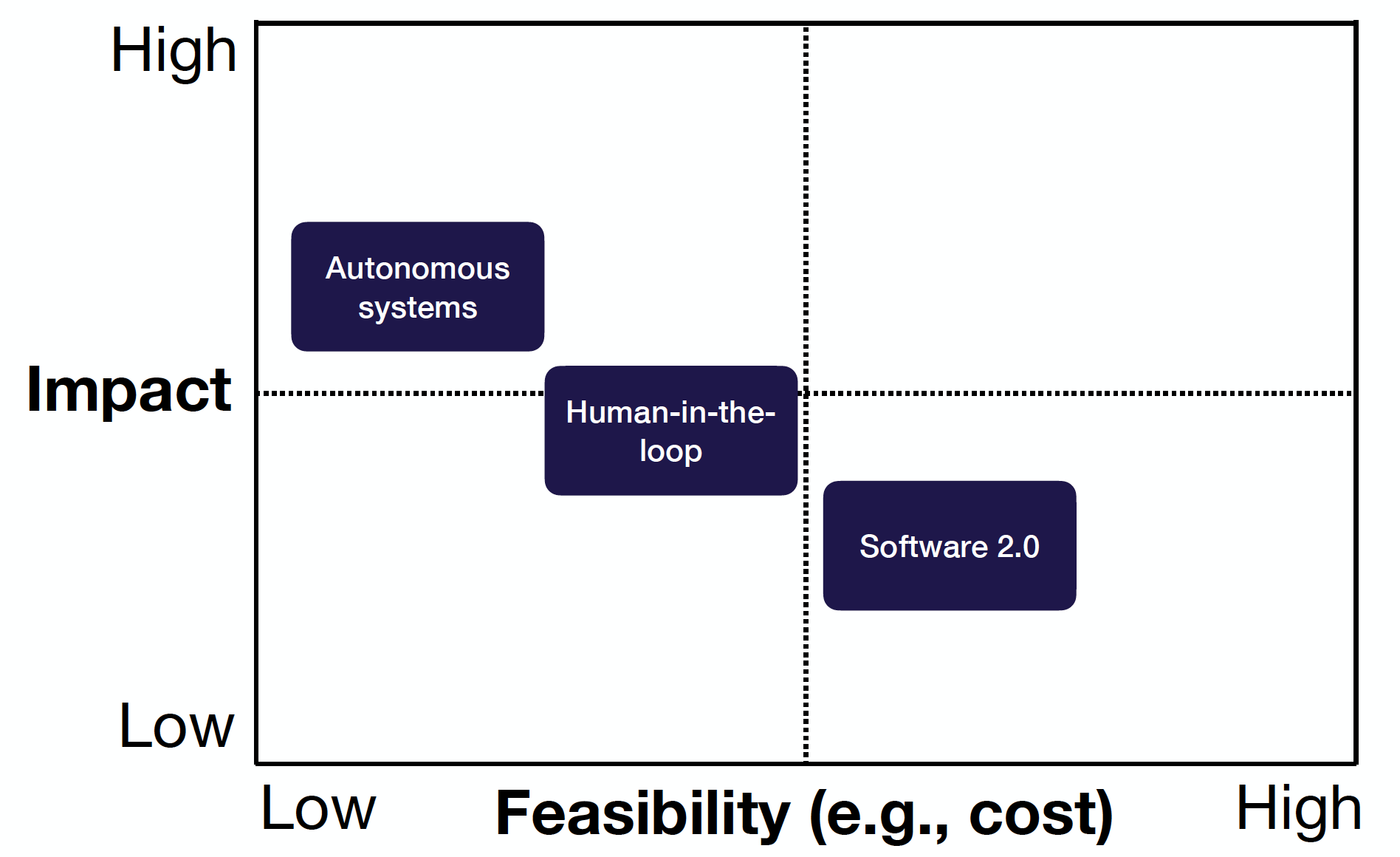

To prioritize projects to work on, you want to find high-impact problems and assess the potential costs associated with them. The picture below shows a general framework that encourages us to target projects with high impact and high feasibility.

High Impact

There are no silver bullets to find high-impact ML problems to work on, but here are a few useful mental models:

-

Where can you take advantage of cheap prediction?

-

Where is there friction in your product?

-

Where can you automate complicated manual processes?

-

What are other people doing?

Cheap Prediction

In the book “Prediction Machines,” the authors (Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb) come up with an excellent mental model on the economics of Artificial Intelligence: As AI reduces the cost of prediction and prediction is central for decision making, cheap predictions would be universal for problems across business domains. Therefore, you should look for projects where cheap predictions will have a huge business impact.

Product Needs

Another lens is to think about what your product needs. In the article “Three Principles for Designing ML-Powered Products,” the Spotify Design team emphasizes the importance of building ML from a product perspective and looking for parts of the product experience with high friction. Automating those parts is exactly where there is a lot of impact for ML to make your business better.

ML Strength

In his popular blog post “Software 2.0,” Andrej Karpathy contrasts software 1.0 (which are traditional programs with explicit instructions) and software 2.0 (where humans specify goals, while the algorithm searches for a program that works). Software 2.0 programmers work with datasets, which get compiled via optimization — which works better, more general, and less computationally expensive. Therefore, you should look for complicated rule-based software where we can learn the rules instead of programming them.

Inspiration From Others

Instead of reinventing the wheel, you can look at what other companies are doing. In particular, check out papers from large frontier organizations (Google, Facebook, Nvidia, Netflix, etc.) and blog posts from top earlier-stage companies (Uber, Lyft, Spotify, Stripe, etc.).

Here is a list of excellent ML use cases to check out (credit to Chip Huyen’s ML Systems Design Lecture 2 Note):

-

Human-Centric Machine Learning Infrastructure at Netflix (Ville Tuulos, InfoQ 2019)

-

2020 state of enterprise machine learning (Algorithmia, 2020)

-

Using Machine Learning to Predict Value of Homes On Airbnb (Robert Chang, Airbnb Engineering & Data Science, 2017)

-

Using Machine Learning to Improve Streaming Quality at Netflix (Chaitanya Ekanadham, Netflix Technology Blog, 2018)

-

150 Successful Machine Learning Models: 6 Lessons Learned at Booking.com (Bernardi et al., KDD, 2019)

-

How we grew from 0 to 4 million women on our fashion app, with a vertical machine learning approach (Gabriel Aldamiz, HackerNoon, 2018)

-

Machine Learning-Powered Search Ranking of Airbnb Experiences (Mihajlo Grbovic, Airbnb Engineering & Data Science, 2019)

-

From shallow to deep learning in fraud (Hao Yi Ong, Lyft Engineering, 2018)

-

Space, Time and Groceries (Jeremy Stanley, Tech at Instacart, 2017)

-

Creating a Modern OCR Pipeline Using Computer Vision and Deep Learning (Brad Neuberg, Dropbox Engineering, 2017)

-

Scaling Machine Learning at Uber with Michelangelo (Jeremy Hermann and Mike Del Balso, Uber Engineering, 2019)

-

Spotify’s Discover Weekly: How machine learning finds your new music (Sophia Ciocca, 2017)

High Feasibility

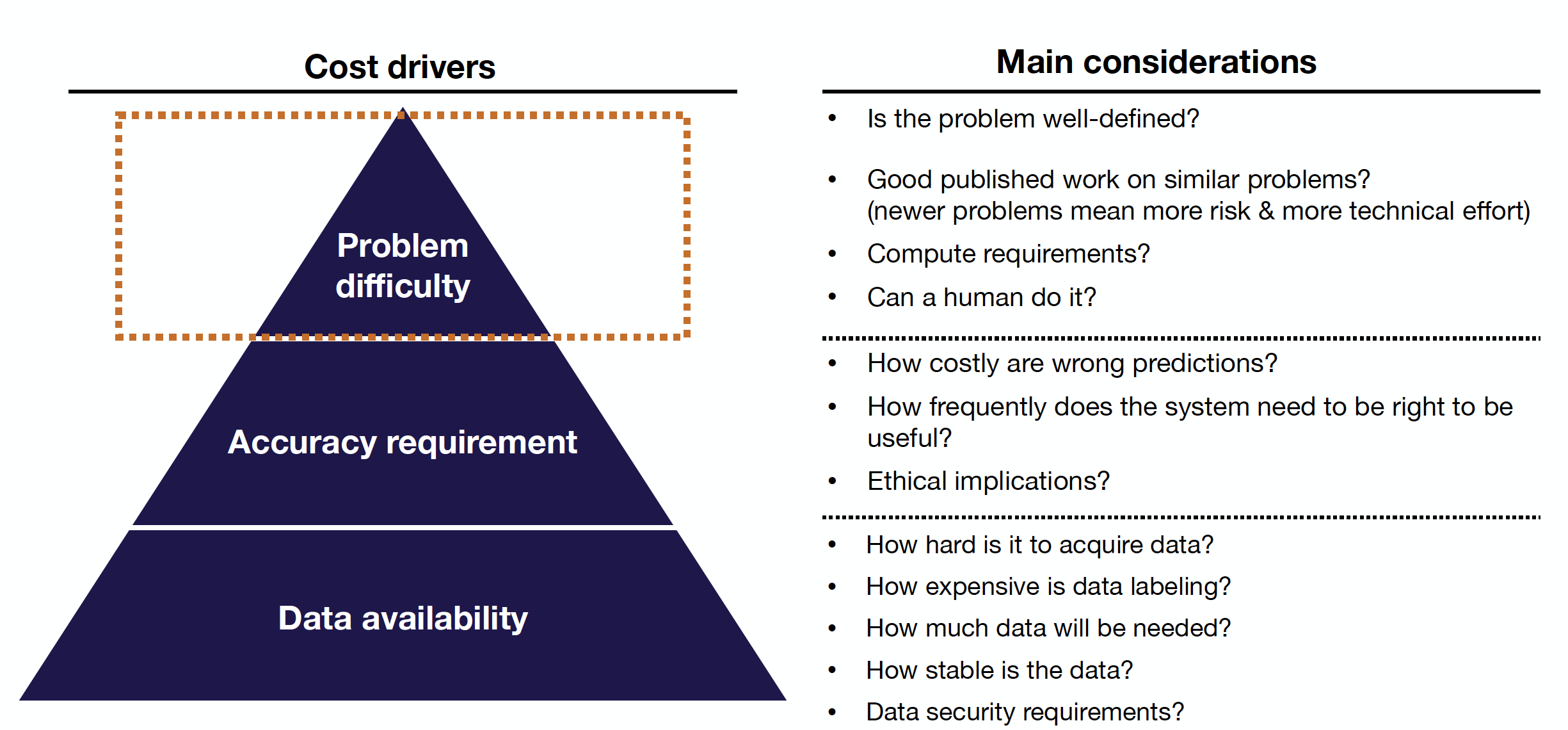

The three primary cost drivers of ML projects in order of importance are data availability, accuracy requirement, and problem difficulty.

Data Availability

Here are the questions you need to ask concerning the data availability:

-

How hard is it to acquire data?

-

How expensive is data labeling?

-

How much data will be needed?

-

How stable is the data?

-

What are the data security requirements?

Accuracy Requirement

Here are the questions you need to ask concerning the accuracy requirement:

-

How costly are wrong predictions?

-

How frequently does the system need to be right to be useful?

-

What are the ethical implications?

It is worth noting that ML project costs tend to scale super-linearly in the accuracy requirement. The fundamental reason is that you typically need a lot more data and more high-quality labels to achieve high accuracy numbers.

Problem Difficulty

Here are the questions you need to ask concerning the problem difficulty:

-

Is the problem well-defined?

-

Is there good published work on similar problems?

-

What are the computing requirements?

-

Can a human do it?

So what’s still hard in machine learning? As a caveat, it’s historically very challenging to predict what types of problems will be difficult for ML to solve in the future. But generally speaking, both unsupervised learning and reinforcement learning are still hard, even though they show promise in limited domains where tons of data and compute are available.

Zooming into supervised learning, here are three types of hard problems:

-

Output is complex: These are problems where the output is high-dimensional or ambiguous. Examples include 3D reconstruction, video prediction, dialog systems, open-ended recommendation systems, etc.

-

Reliability is required: These are problems where high precision and robustness are required. Examples include systems that can fail safely in out-of-distribution scenarios, is robust to adversarial attacks, or needs to tackle highly precise tasks.

-

Generalization is required: These are problems with out-of-distribution data or in the domains of reasoning, planning, and causality. Examples include any systems for self-driving vehicles or any systems that deal with small data.

Finally, this is a nice checklist for you to run an ML feasibility assessment:

-

Are you sure that you need ML at all?

-

Put in the work upfront to define success criteria with all of the stakeholders.

-

Consider the ethics of using ML.

-

Do a literature review.

-

Try to build a labeled benchmark dataset rapidly.

-

Build a minimal viable product with manual rules

-

Are you “really sure” that you need ML at all?

4 - Archetypes

So far, we’ve talked about the lifecycle and the impact of all machine learning projects. Ultimately, we generally want these projects, or applications of machine learning, to be useful for products. As we consider how ML can be applied in products, it’s helpful to note that there are common machine learning product archetypes or recurrent patterns through which machine learning is applied to products. You can think of these as “mental models” you can use to assess your project and easily prioritize the needed resources.

There are three common archetypes in machine learning projects: Software 2.0, Human-in-the-loop, and autonomous systems. They are shown in the table below, along with common examples and questions. We’ll dive deeper into each.

| Archetype | Examples | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Software 2.0 | - Improve code completion in IDE - Build customized recommendation system - Build a better video game AI |

- Do your models truly improve performance? - Does performance improvement generate business value? - Do performance improvements lead to a data flywheel? |

| Human-in-the-loop | - Turn sketches into slides - Email auto-completion - Help radiologists do job faster |

- How good does the system need to be to be useful? - How can you collect enough data to make it good? |

| Autonomous Systems | - Full self-driving - Automated customer support - Automated website design |

- What is an acceptable failure rate for the system? - How can you guarantee that it won’t exceed the failure rate? - How inexpensively can you label data from the system? |

Software 2.0

Software 2.0, which we previously alluded to from the Karpathy article, is defined as “augmenting existing rules-based or deterministic software with machine learning, a probabilistic approach.” Examples of this are taking a code completer in an IDE and improving the experience for the user by adding an ML component. Rather than suggesting a command based solely on the leading characters the programmer has written, you might add a model that suggests commands based on previous commands the programmer has written.

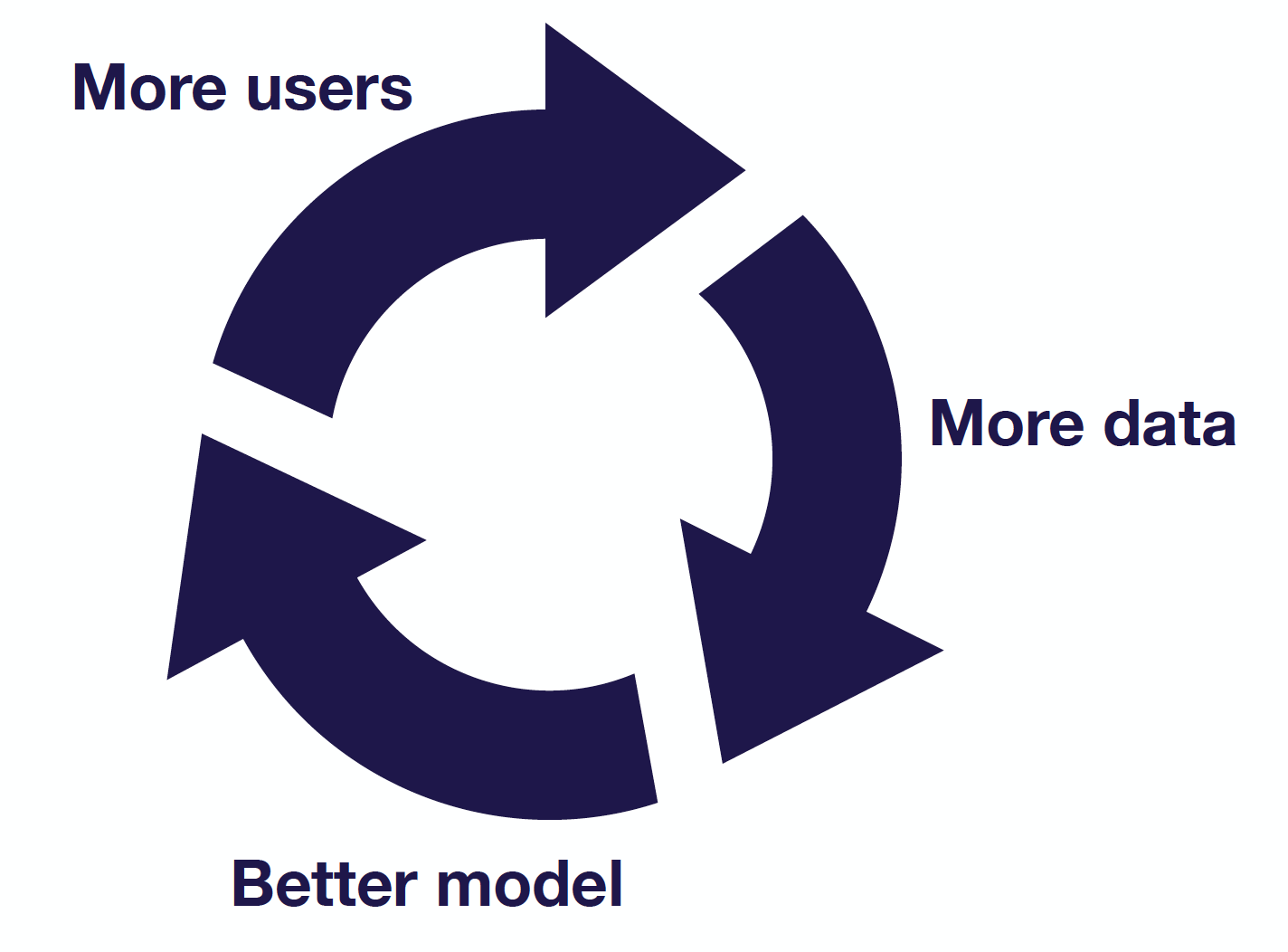

As you build a software 2.0 project, strongly consider the concept of the data flywheel. For certain ML projects, as you improve your model, your product will get better and more users will engage with the product, thereby generating more data for the model to get even better. It’s a classic virtuous cycle and truly the gold standard for ML projects.

In embarking on creating a data flywheel, critically consider where the model could fail in relation to your product. For example, do more users lead to collecting more data that is useful for improving your model? An actual system needs to be set up to capture this data and ensure that it's meaningful for the ML lifecycle. Furthermore, consider whether more data will lead to a better model (your job as an ML practitioner) or whether a better model and better predictions will actually lead to making the product better. Ideally, you should have a quantitative assessment of what makes your product “better” and map model improvement to it.

Human-in-the-Loop (HIL)

HIL systems are defined as machine learning systems where the output of your model will be reviewed by a human before being executed in the real world. For example, consider translating sketches into slides. An ML algorithm can take a sketch’s input and suggest to a user a particular slide design. Every output of the ML model is considered and executed upon by a human, who ultimately has to decide on the slide’s design.

Autonomous Systems

Autonomous systems are defined as machine learning systems where the system itself makes decisions or engages in outputs that are almost never reviewed by a human. Canonically, consider the self-driving car!

Feasibility

Let’s discuss how the product archetypes relate back to project priority. In terms of feasibility and impact, the two axes on which we consider priority, software 2.0 tends to have high feasibility but potentially low impact. The existing system is often being optimized rather than wholly replaced. However, this status with respect to priority is not static by any means. Building a data flywheel into your software 2.0 project can improve your product’s impact by improving the model’s performance on the task and future ones.

In the case of human-in-the-loop systems, their feasibility and impact sit squarely in between autonomous systems and software 2.0. HIL systems, in particular, can benefit disproportionately in their feasibility and impact from effective product design, which naturally takes into account how humans interact with technology and can mitigate risks for machine learning model behavior. Consider how the Facebook photo tagging algorithm is implemented. Rather than tagging the user itself, the algorithm frequently asks the user to tag themselves. This effective product design allows the model to perform more effectively in the user’s eye and reduces the impact of false classifications. Grammarly similarly solicits user input as part of its product design through offering explanations. Finally, recommender systems also implement this idea. In general, good product design can smooth the rough edges of ML (check out the concept of designing collaborative AI).

There are industry-leading resources that can help you merge product design and ML. Apple’s ML product design guidelines suggest three key questions to anyone seeking to put ML into a product:

-

What role does ML play in your product?

-

How can you learn from your users?

-

How should your app handle mistakes?

Associated with each question is a set of design paradigms that help address the answers to each question. There are similarly great resources from Microsoft and Spotify.

Finally, autonomous systems can see their priority improved by improving their feasibility. Specifically, you can add humans in the loop or reduce the system’s natural autonomy to improve its feasibility. In the case of self-driving cars, many companies add safety drivers as guardrails to improve autonomous systems. In Voyage’s case, they take a more dramatic approach of constraining the problem for the autonomous system: they only run self-driving cars in senior living communities, a narrow subset of the broader self-driving problem.

5 - Metrics

So far, we’ve talked about the overall ideas around picking projects and structuring them based on their archetypes and the specific considerations that go into them. Now, we’ll shift gears and be a little more tactical to focus on metrics and baselines, which will help you execute projects more effectively.

Choosing a Metric

Metrics help us evaluate models. There’s a delicate balance between the real world (which is always messy and multifaceted) and the machine learning paradigm (which optimizes a single metric) in choosing a metric. In practical production settings, we often care about multiple dimensions of performance (i.e., accuracy, speed, cost, etc.). The challenge is to reconcile all the possible evaluation methods with the reality that ML systems work best at optimizing a single number. How can we balance these competing needs in building an ML product?

As you start evaluating models, choose a single metric to focus on first, such as precision, accuracy, recall, etc. This can serve as an effective first filter of performance. Subsequently, you can put together a formula that combines all the metrics you care about. Note that it’s important to be flexible and regularly update this formula as your models or the requirements for the product change.

Combining Metrics

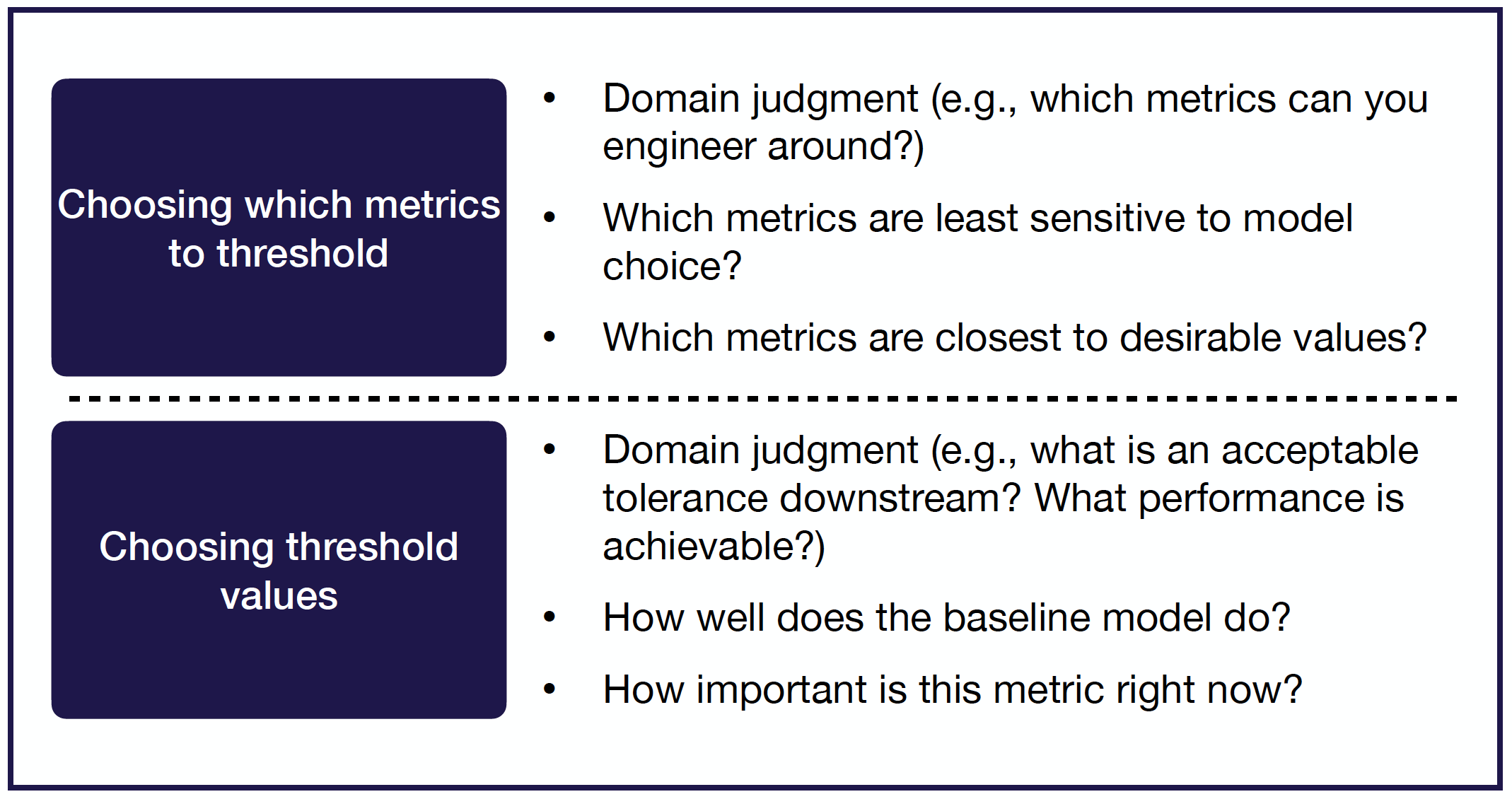

Two simple ways of combining metrics into a formula are averaging and thresholding.

Averaging is less common but easy and intuitive; you can just take a simple average or a weighted average of the model’s metrics and pick the highest average.

More practically, you can apply a threshold evaluation to the model’s metrics. In this method, out of n evaluation metrics, you threshold n-1 and optimize the nth metric. For example, if we look at a model’s precision, memory requirement, and cost to train, we might threshold the memory requirement (no more than X MB) and the cost (no more than $X) and optimize precision (as high as possible). As you choose which metrics to threshold and what to set their threshold values to, make sure to consider domain-specific needs and the actual values of the metrics (how good/bad they might be).

6 - Baselines

In any product development process, setting expectations properly is vital. For machine learning products, baselines help us set expectations for how well our model will perform. In particular, baselines set a useful lower bound for our model’s performance. What’s the minimum expectation we should have for a model’s performance? The better defined and clear the baseline is, the more useful it is for setting the right expectations. Examples of baselines are human performance on a similar task, state-of-the-art models, or even simple heuristics.

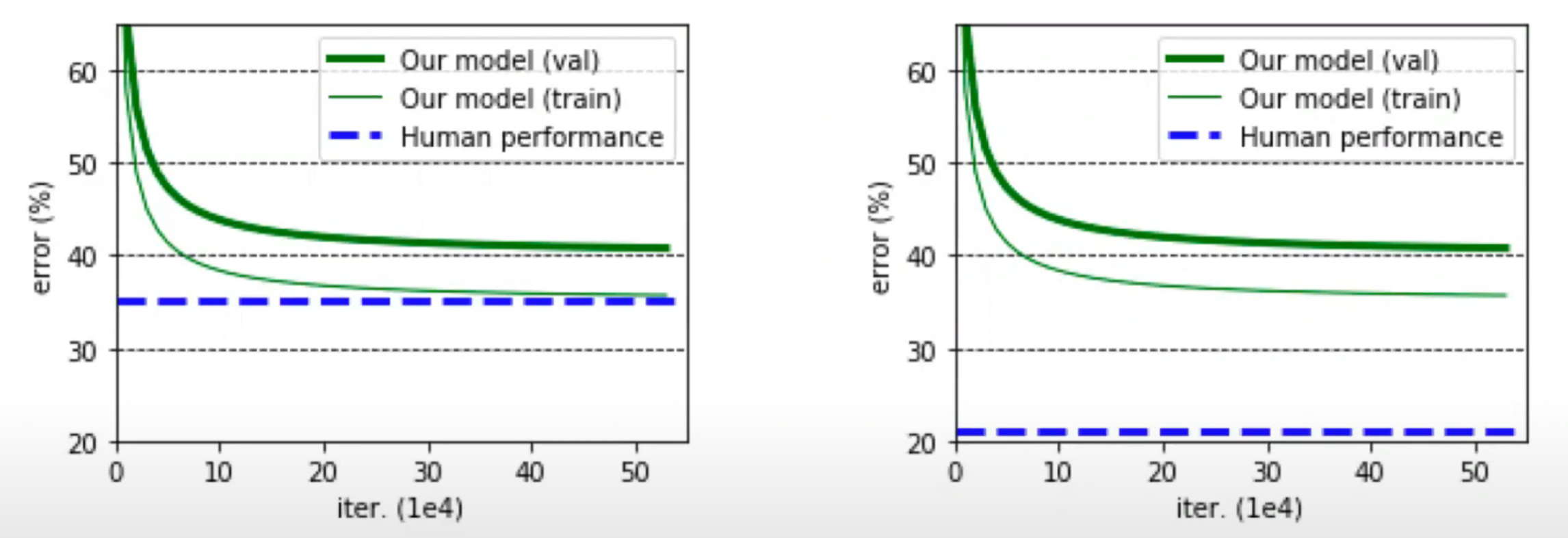

Baselines are especially important for helping decide the next steps. Consider the example below of two models with the same loss curve but differing performance with respect to the baseline. Clearly, they require different action items! As seen below, on the left, where we are starting to approach or exceed the baseline, we need to be mindful of overfitting and perhaps incorporate regularization of some sort. On the right, where the baseline hugely exceeds our model’s performance, we clearly have a lot of work to do to improve the model and address its underfitting.

There are a number of sources to help us define useful baselines. Broadly speaking, there are external baselines (baselines defined by others) or internal baselines you can define yourself. With internal baselines, in particular, you don’t need anything too complicated, or even something with ML! Simple tests like averaging across your dataset can help you understand if your model is achieving meaningful performance. If your model can’t exceed a simple baseline like this, you might need to really re-evaluate the model.

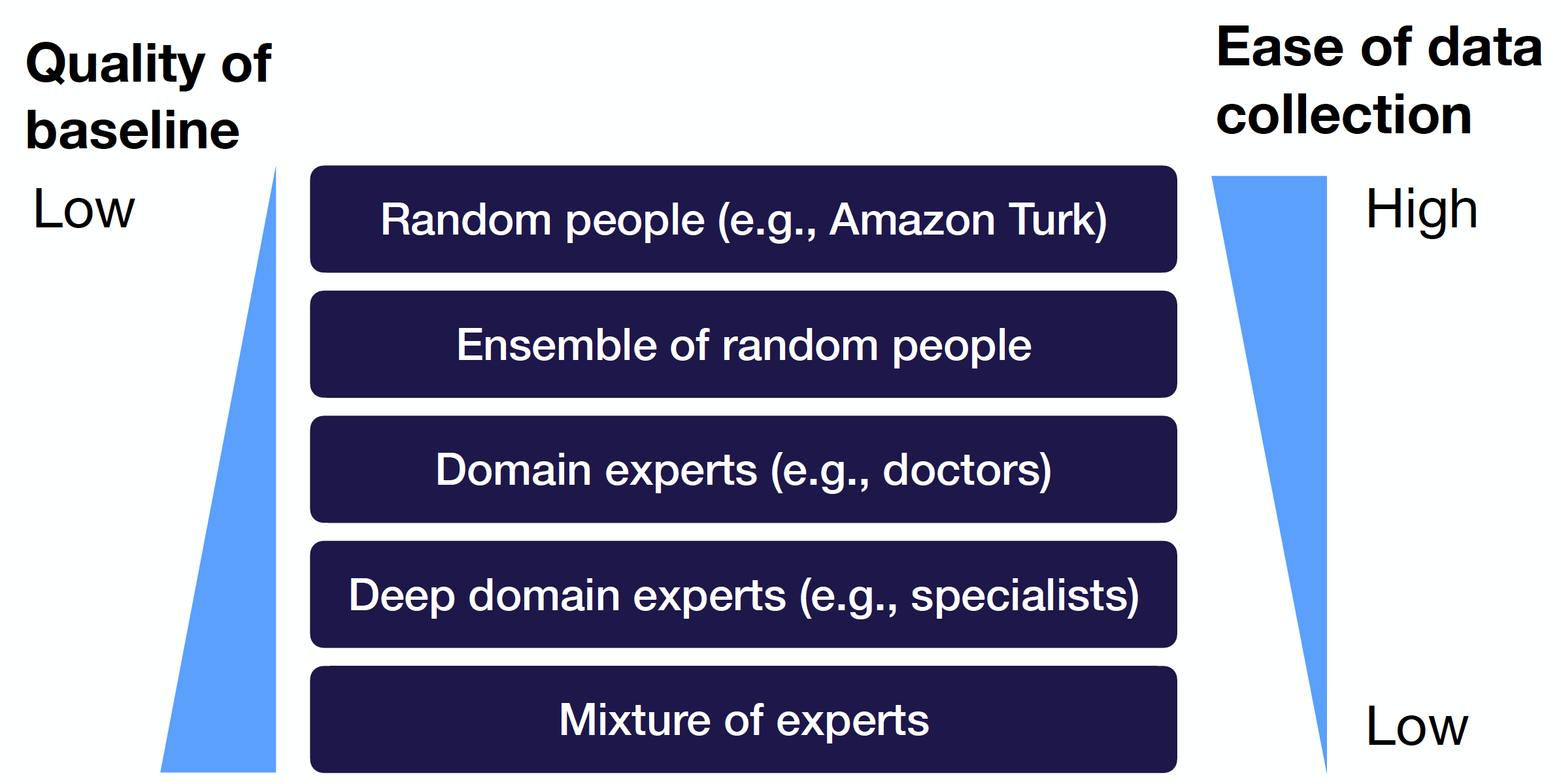

Human baselines are a particularly powerful form of baseline since we often seek to replace or augment human actions. In creating these baselines, note that there’s usually an inverse relationship between the quality of the baseline and the ease of data collection. In a nutshell, the harder it is to get a human baseline, the better and more useful it probably is.

For example, a Mechanical Turk-created baseline is easy to generate nowadays, but the quality might be hit or miss because of the variance in annotators. However, trained, specialized annotators can be hard to acquire, but the specificity of their knowledge translates into a great baseline. Choosing where to situate your baseline on this range, from low quality/easy to high quality/hard, depends on the domain. Concentrating data collection strategically, ideally in classes where the model is least performant, is a simple way of improving the quality of the baseline.

TLDR

-

Machine learning projects are iterative. Deploy something fast to begin the cycle.

-

Choose projects with high impact and low cost of wrong predictions.

-

The secret sauce to make projects work well is to build automated data flywheels.

-

In the real world, you care about many things, but you should always have just one to work on.

-

Good baselines help you invest your effort the right way.

Further Resources

-

Andrew Ng’s “Machine Learning Yearning”

-

Andrej Kaparthy’s “Software 2.0”

-

Agrawal, Gans, and Goldfarb’s “The Economics of AI”

-

Chip Huyen’s “Introduction to Machine Learning Systems Design”

-

Google’s “Rules of Machine Learning”

We are excited to share this course with you for free.

We have more upcoming great content. Subscribe to stay up to date as we release it.

We take your privacy and attention very seriously and will never spam you. I am already a subscriber